No balm in Gilead in Atwood's "The Testaments"

The long-awaited sequel to "The Handmaid's Tale" is taut and tart -- like its author

Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” appeared just as I was entering adulthood. I read it not terribly long after its 1985 publication and I was utterly chilled by its depiction of a totalitarian religious state that completely controls women’s bodies and minds in the country formerly known as the United States.

By now, reams have been written about that book and its current cultural relevance as religious voters continue to gain strength, as women’s #MeToo stories continue to be shrugged off ( I’m lookin’ at you, Brett Kavanaugh) and as reproductive rights face greater threats. We’ve all seen the pictures of protesters dressed as Handmaids in red cloaks and face-obscuring white bonnets at Congressional hearings and marches. So I won’t bore you with that.

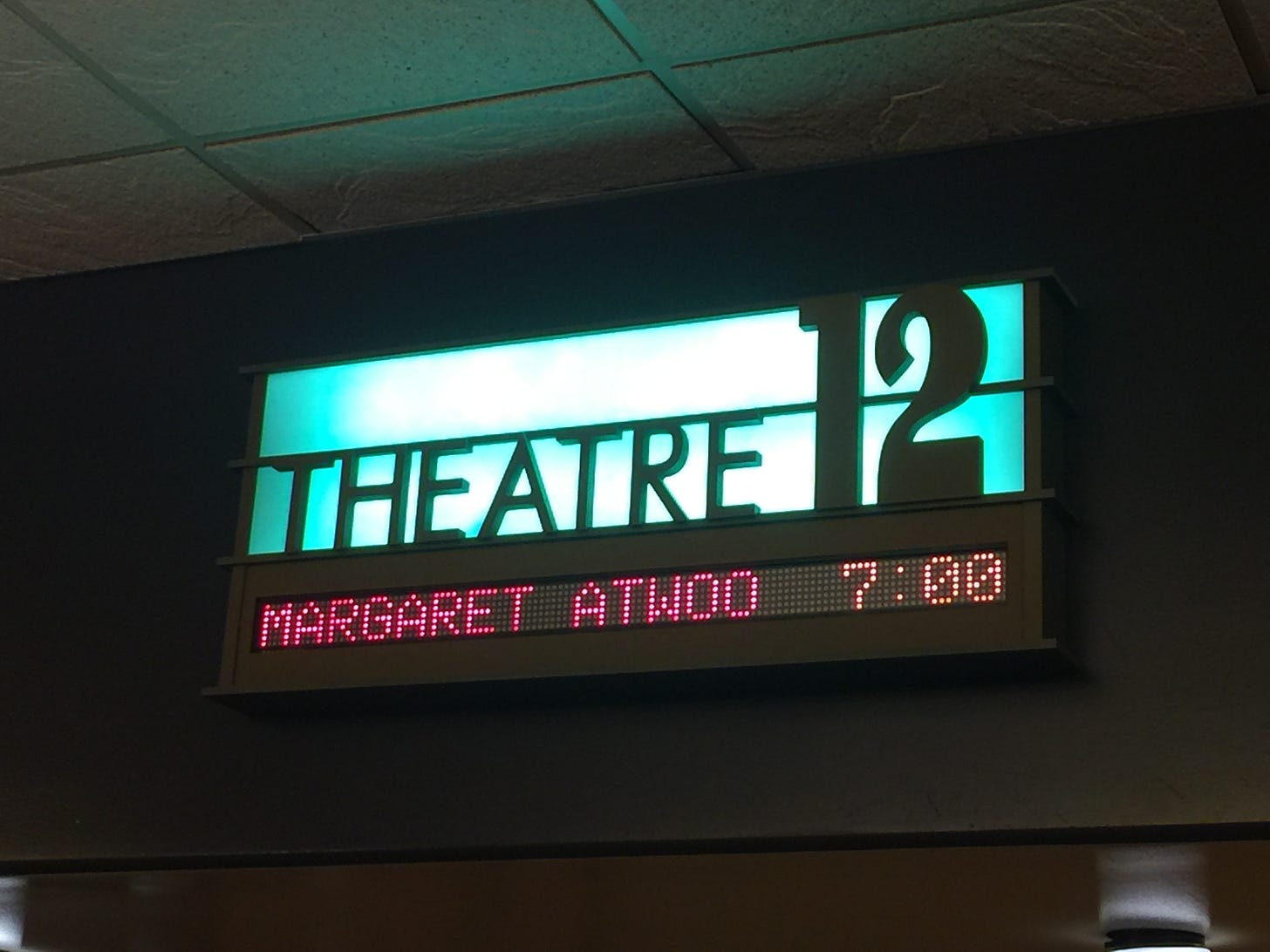

Instead, I want to look at Atwood’s sequel, “The Testaments,” which was published on Tuesday (Sept. 9) to great fanfare and anticipation. Last night I attended a live theatrical event beamed (almost) live from London’s National Theater that featured a lengthy interview with Atwood, who is Canadian, framed by readings from the new work by actresses Sally Hawkins, Lucy James and — most deliciously — Ann Dowd, who plays the terrifying Aunt Lydia in the Hulu television series of “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

Don’t worry — no spoilers lurk below. I want to talk about the two books’ relation to religion and what Atwood has said about that.

Gilead is run by religious zealots who seem to have tossed out the New Testament for the Old. The young girls and women of Gilead are raised without stories of unconditional love or care for the least of these or any other idea associated with Jesus. Instead, they are brought up on stories out of the darker (and more problematic) books of the bible, in which women fare poorly, to put it mildly.

Take one of the central biblical touchstones of “The Testaments” — the story of the runaway concubine from Judges 19. An angry crowd demands a man, a stranger in their town, be given over to them so they can “have sex with him.” Instead, he turns over his concubine and the crowd of men rapes her to death. The man then cuts her up in 12 pieces, one for each of the tribes of Israel, and asks for justice — not for her, but for the damage to his property.

The owner of the house went outside and said to them, “No, my friends, don’t be so vile. Since this man is my guest, don’t do this outrageous thing. 24 Look, here is my virgin daughter, and his concubine. I will bring them out to you now, and you can use them and do to them whatever you wish. But as for this man, don’t do such an outrageous thing.”

Both “The Handmaid’s Tale” and “The Testaments” are full of horrors like this and Atwood has been accused of being anti-religion. But she insists that she is not. Rather, she has said, she is anti-totalitarian.

In 2017, a writer named Anna Czarnik-Niemeyer asked Atwood, who is agnostic, about religion in “The Handmaid’s Tale.” According to Czarnik-Niemeyer, this is what she said:

Religion has been- and is in other parts of the world today- used as a hammer to whack people on the heads with.

But it also has been- and is today- a sustaining set of beliefs and community that gets people through those things.

So, in my book, I have the regime doing what totalitarian regimes do, which is eliminating the competition. They get rid of all the other religions as much as they can, and some of them go underground. Noteworthily, of course, the Quakers take the role that they have before, setting up underground escape routes for people. So [religion] has always had those two kinds of functions. And that is why the handmaid, in the book, she has her version of the Lord’s Prayer, which a lot of people don’t spot, but careful readers do.

That’s how it goes, and I don’t think that cultures in which the totalitarianism happens to be religious, I don’t think that’s a comment on religion, I think it’s a comment on totalitarianism. And there have been some perfectly respectable totalitarianisms that have been atheist. So that is not the factor.

I’ll take her at her word on that. Still, the twisted religion in Gilead — which Atwood never links to a specific denomination — is as fascinating as it is frightening and never seems — to this reader, at least — far-fetched. You can see its echoes today in The Family, the secretive, fundamentalist Christian at work behind the scenes in Washington DC and abroad.

One thing I found surprising about last night’s live-ish interview with Atwood (which wasn’t all that great of an interview; Atwood seems to be tough on interviewers, scoffing a bit at what she seems to deem obvious questions — but then, she’s done a lot of them and might be tired) was that she believes both “The Handmaid’s Tale” and “The Testaments” are “optimistic.”

Gilead, she reminded the audience, is short-lived, as “The Handmaid’s Tale” is (fictionally) reconstructed from evidence and testimonies of its victims. And, she continued, she mentions that Quakers are working to spirit women out of Gilead via the “Underground Femaleroad.” She also notes that the unnamed Handmaid of the book (called June in the Hulu series) has her own version of the Lord’s Prayer:

My God. Who Art in the Kingdom of Heaven, which is within.

I wish you would tell me Your Name, the real one I mean. But You will do as well as anything.

I wish I knew what You were up to. But whatever it is, help me to get through it, please. Though maybe it is not Your doing; I don’t believe for an instant that what’s going on out there is what You meant.

I don’t either (and I think that’s a damn fine prayer). As for the optimism in “The Testaments,” Atwood finds it — and the reader will too — in the voices of the two young women who deliver their testimonies of the title. She said she finds similar optimism in the attitude young people have towards the climate crisis, which she called singularly threatening to women and children because when resources get scarce, they’re the ones who suffer first.

I am both enthralled and repelled by “The Testaments,” and I think that is as it should be. I have not yet finished it, but have spent two very late nights poring over it. Like “Handmaid,” I think it is one I will return to over and over again. Maybe some of its optimism will rub off on me, eventually.